“What should we, as members of Congress, be doing about artificial intelligence?” asks Diego Caicedo, a young Colombian congressman, in a video posted to his Instagram profile. Standing beside him is Pablo Nieto, another Colombian, who answers: “Create frameworks that promote AI” and “listen to all stakeholders.”

There was nothing casual about the exchange—not the setting, not the speakers, and certainly not what was said.

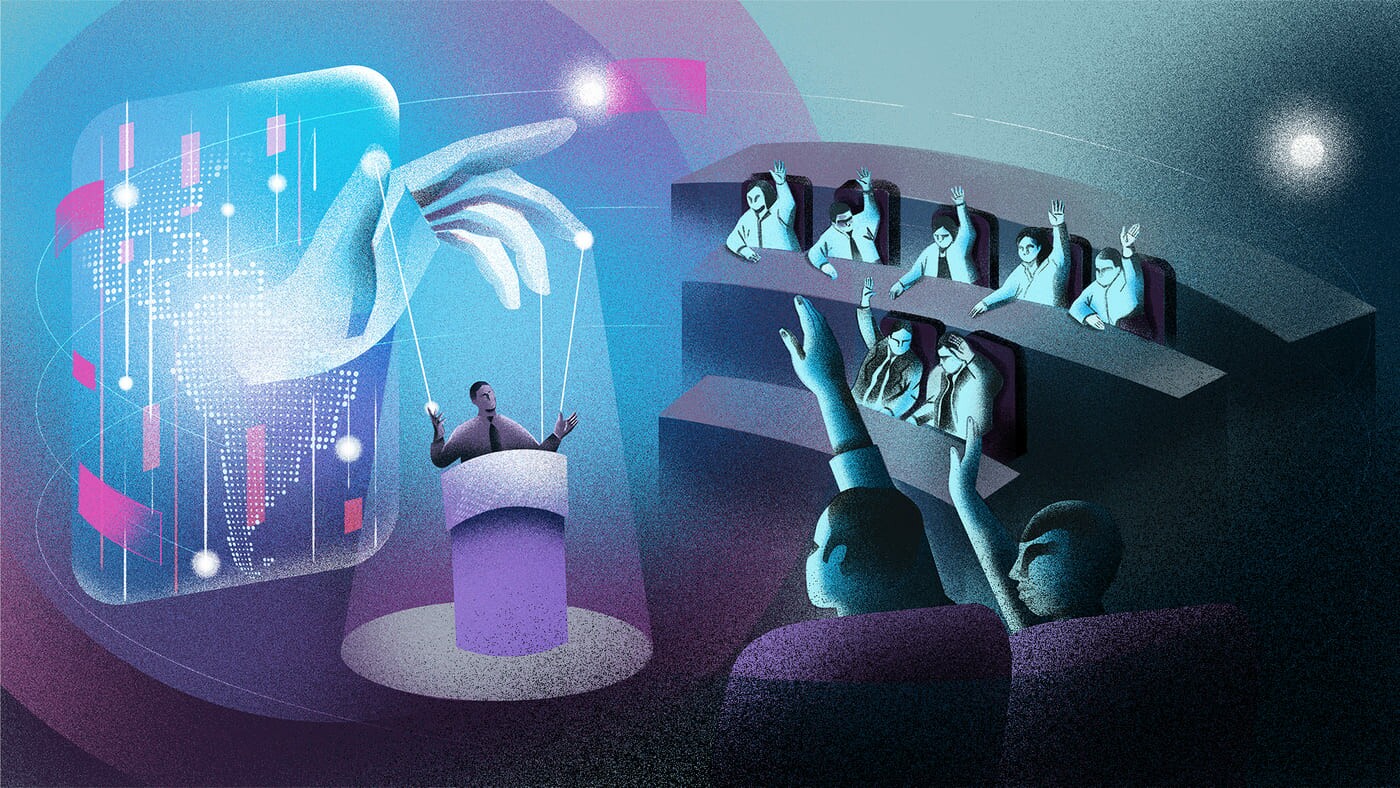

Both men are part of a broader web of influence through which Big Tech companies like Google, Amazon, Meta, and Microsoft shape public policy in Latin America. Other players in this quiet, high-stakes game include lawmakers who echo tech-friendly arguments, well-paid lobbyists who push corporate narratives, and experts or former officials who frame private interests as matters of public good.

When tech companies prefer not to put their own lobbyists in the spotlight, they turn to intermediaries: law firms, industry associations, and policy groups. These entities host international conferences, meet regularly with public officials, produce studies designed to “enlighten” ministries, and submit policy proposals under the banner of national development.

As Andrés Hernández, Executive Director of Transparencia por Colombia, explained to this reporting alliance, their strategy is simple: gain “access to decision-makers and to any mechanism that allows them to influence decisions.”

None of this is illegal—and none of it is new. In many ways, it mirrors the tactics of other powerful multinationals, like mining, tobacco or pharmaceutical companies.

But there is a crucial difference. Where those companies could influence a single sector, Big Tech has embedded itself into nearly every aspect of modern life. From talking to family and scheduling appointments to getting directions, holding virtual meetings, or reading the news—avoiding tech platforms takes conscious effort. And their influence is only growing, as artificial intelligence becomes woven into everything we do.

We’re talking about Alphabet—the parent company of Google, YouTube, and dozens of tools for navigation, learning, research, even investigative journalism. By its own definition, Alphabet’s mission is “to organize the world’s information and make it universally accessible and useful.” Today, “to google” is a verb in most languages. And while there are other search engines, none are as deeply embedded in the daily routines of Latin Americans.

We’re also talking about Meta, the company behind WhatsApp, Facebook, and Instagram—whose stated goal is “to build the future of human connection and the technology that makes it possible.” People have also invented the verb “to whatsapp” to mean “send a message.” Every day, millions share their lives on Facebook and Instagram. Meta’s platforms know their users inside and out and sell that knowledge to advertisers—whether they’re selling soap or running for office—down to the level of emotional states, making it easier to market products or ideas tailored to each user. According to the company’s own reports, on an average day in December 2024, some 3.35 billion people were using at least one Meta platform. That’s nearly half the global population.

Such influence on politics, human rights, social welfare, public health, the mental health of young people, the economy, and the simple fact that these companies are practically indispensable to function in today’s life, would lead one to think that regulating them is crucial for any country.

But as this journalistic investigation—The Invisible Hand of Big Tech, led by the Brazilian outlet Agência Pública and the Centro Latinoamericano de Investigación Periodística (CLIP), together with 15 other media outlets in 13 countries—has shown, regulating the tech giants has been anything but easy. They have bottomless pockets to fight every battle. Their algorithms hide behind trade secrecy, and sophisticated expertise is needed to regulate them without sliding into censorship. And they resist at all costs any local rule that might undermine their global business model.

A database collectively built from publicly available online information, freedom of information requests, interviews with dozens of sources in governments, congresses, and tech companies, as well as with experts and academics, documented 2,977 concrete influence actions in ten countries and the European Union, most of them between 2019 and June 2025. These involved 1,516 direct or indirect representatives of the tech companies who, in defense of the digital industry’s positions, interacted with 2,508 public officials—from legislators, regulators, and ministers to directors of public schools and hospitals. (See dashboard and methodology board created from the database.)

This investigation also found that the need to curb the unwanted impacts of Big Tech is so great that, in just eleven countries and the European Union, governments, legislators, or citizens have introduced at least 801 bills since 2019. These initiatives seek to improve moderation in spaces where children and teenagers gather; block accounts that spread hate with impunity; enforce national electoral or data protection laws; hold platforms accountable for harmful content; and punish damaging uses of artificial intelligence, among other causes.

The journalistic alliance likewise found 315 legal cases in just four countries, recorded since 2022, tied to conflicts with tech companies. These lawsuits range from a citizen’s complaint over the misuse of a video or image, to claims for failing to regulate harmful content or to comply with privacy laws. Tech companies, for their part, have also sued governments to oppose sanctions or rules that restrict their operations.

This alliance sent detailed questionnaires to Big Tech companies about their lobbying activities in several countries. The corporations responded with general statements acknowledging their interactions with policymakers in issues relevant to their products and businesses, and claiming these interactions comply with all relevant ethical and regulatory guidelines. Find a document detailing the companies’ responses here.

In this cross-border story of The Invisible Hand of Big Tech, we reveal in detail how several lobbying operations unfolded in Latin America by some of the companies that most shape people’s daily lives. Where were their battles fought? Who makes up their squads of lobbyists and influence agents in certain countries?

A Telling Photo

The meeting where Colombian congressman Caicedo interviewed his compatriot Nieto, cited above, was called Digiecon 2025. It took place in April of this year in Mexico City and brought together at least 15 legislators from Latin Americal with executives from TikTok, Meta, Rappi, Mercado Libre and Google, among others, to debate “digital economy” and “social and economic development.”

It was organized by the Latin American Internet Association (ALAI), the industry group representing the tech companies, which invited Caicedo—according to what he told Cuestión Pública, the Colombian outlet that is part of this alliance.

Congress members present at Digiecon 2025 included Brazilian deputies Any Ortiz, Rodrigo Valadares, and David Soares; four Argentine legislators (Juan Manuel López, Dahiana Fernández Molero, Karina Banfi, and Santiago Santurio); four additional Colombian legislators besides Caicedo (Ciro Rodríguez Pinzón, Carlos Guevara, Irma Luz Herrera, and Daniel Restrepo Carmona); three Chilean legislators (Leonardo Soto Ferrada, Francisco Chahuán, and Paula Labra); and others from Guatemala (Manuel De Jesús Archila Cordón), Costa Rica (Kattia Cambronero Aguiluz), and Peru (José Ernesto Cueto). This journalistic alliance was able to reconstruct the list of attendees using photos of the event and other records from social media. Additional public officials from these and other Latin American countries also took part.

We found that some of these guests are now central figures in digital policy debates in their legislatures, either pushing—and at times blocking—bills, or advancing the interests of tech companies within their parliaments. That photo from the event thus becomes a powerful metaphor for how the tech giants’ tentacles extend across the continent.

Representative Caicedo, for example, in September 2024 pushed for the creation of an ad hoc commission to study the pending bills related to artificial intelligence, just as another committee was preparing to do the very same thing. Although the move was officially aimed, according to Congress, at unifying various regulatory initiatives, it failed to achieve that goal. Colombian senator Alirio Uribe, who has promoted several of those bills, told Cuestión Pública and CLIP, members of this alliance, that the AI commission “was created to obstruct all the projects. What they did was take all the bills, review them, and then present us with inane articles.” Since then, only one AI regulation has been passed by the Colombian legislature: a measure that increases penalties for fraud when artificial intelligence tools are used to commit it.

Caicedo did not answer questions from this journalistic partnership about his role in the process of AI bills in the Colombian congress, nor those about his video with Nieto.

Nieto, ALAI’s public policy manager for the Andean region, maintains a permanent presence in Colombia’s Congress. He appears in public consultations and writes legal opinions on bills, but he also organizes open and closed-door events with legislators and has cultivated close relationships with Caicedo and several other Colombian congress members, as this journalistic alliance has verified through public events and social media content. Between October 2023 (when he began working at ALAI) and December 2024, Nieto logged 22 visits to congress members, according to a freedom of information request filed by Cuestión Pública.

In Ecuador, Nieto has also lobbied in favour of the tech companies during the regulatory process following approval of Data Protection Law in 2021. The first regulation, adopted in 2023, was drafted with participation from industry associations but with almost no input from other sectors, according to the outlet Primicias, another partner in this alliance. In 2024, Nieto met with Fabrizio Peralta Díaz, Ecuador’s Superintendent of Data Protection, to discuss specific regulatory issues under the law, according to public records. And in April 2025, Peralta Díaz travelled to Mexico for Digiecon, where he again met with Nieto and with Raúl Echeberría, ALAI’s executive director.

Asked about his relationship with ALAI, Peralta Díaz said Primicias he has not received any pressures from ALAI or any other actor. “I have never received any particular or special request by Pablo (Nieto) other than their request to be listened,” he said. In a statement, ALAI said that “official echanges with governments and officers are held through usual formal channels in each country.”

The Footprint of ALAI

ALAI was founded in 2015 in Montevideo, Uruguay, as an alliance between five technology companies: the Latin American firms Despegar.com, a travel company, and Mercado Libre, an online marketplace; and the U.S. giants Yahoo, Facebook, and Google. Its first executive director, Gonzalo Navarro, said in an interview at the time that the Association sought to “contribute to strengthening the Internet ecosystem, building bridges between the different actors that compose it and developing public policies within our remit.”

Today, among the 14 technology companies on its board are Amazon, AirBnb, and TikTok, as well as the Latin American delivery company Rappi. As recorded in its 2023 financial statements filed with the Uruguayan government, each of these companies pays an annual membership fee of up to $50,000, with some also contributing additional amounts to support specific projects. That year ALAI reported revenues of more than one million dollars, all of them coming from contributions by technology companies, and administrative expenses of $711,000.

ALAI staunchly defends the commercial interests of its member companies before congresses, courts, and regulatory entities across the region. The Association, for example, opposed tourism regulations in Colombia that sought to limit short-term rentals promoted by AirBnb. In Mexico, it pushed for “a balanced regulatory framework” in debates about the labor rights of workers for companies such as Rappi — an elegant way of resisting measures that would have required platforms to provide formal labor contracts to their workers.

The association said “it does not represent the interests of specific companies or lobby on behalf of specific companies, but rather, like any other sectoral business chamber, represents the interests of the sector in general.”

In Brazil, it has also criticized similar proposals, and its positions have found a receptive audience among some of the legislators who attended Digiecon 2025 in Mexico City. Brazilian congresswoman Any Ortiz announced on her Instagram that she was there to discuss a bill of law to regulate the digital market, for which she serves as rapporteur. “This ecosystem can drive small, medium, and large companies, generating more innovation, competitiveness, and opportunities,” she wrote in her post.

A month later, on May 7 of this year, Ortiz requested a public hearing to debate a study published by the Latin American Internet Association (ALAI) in September 2024, related to that bill. The study concluded that the proposed regulation would be harmful to Brazil’s economy and could impose additional costs on users of more than R$2 billion (equivalent to US$365 million).

Thirteen days later, Sérgio Garcia Alves, ALAI’s manager in Brazil, said — seated next to Ortiz — that the initiative could cause “a spiral of costs,” since it contemplated a 2% tax on the operational revenues of platforms. He also said that the European Union’s Digital Markets Act (DMA), on which the Brazilian bill was modelled, was “an experimental regulatory framework, whose benefits are not yet evident.”

For her part, Ortiz said she had doubts whether the bill was convenient: she not only claimed that some of the DMA’s rules do not apply in Brazil, and would therefore “need to be further developed,” but also warned that the measure “could impact the cost to consumers using digital services.” These were precisely the same points raised by ALAI.

In a response she sent to this alliance, Ortiz said the positions she expressed at the hearing “do not come from a specific entity, but from a broad process of reflection and analysis.” She also said she invited government representatives to participate in the event, but “they decided not to attend.”

Ortiz sought to “listen to all stakeholders” in the regulation of technology markets and that she has “regularly participated in national and international events organized by various entities,” she said. She also stated that the hearing about the ALAI study “was unrelated” to her participation in Digiecon, as it was initially requested in 2024. The congresswoman did not answer who financed her trip to Digiecon, but said it did not generate any costs for the Chamber of Deputies. Read the full response here.

ALAI was also present in Brazil’s discussions on the so-called Fake News bill (2630 of 2020), which sought to regulate digital platforms and was ultimately buried by platform lobbying, as revealed in another story of this investigation. Between March and May 2023, when the bill was about to be voted on in the Chamber of Deputies, the Association published three documents ( 1, 2, 3 )opposing its approval. It argued, for instance, that the text posed a risk of state control over information — a claim that, according to Artur Romeu, head of Reporters Without Borders’ Latin American Office, had no foundation.

“Regulation is not censorship. The bill has been widely debate for years and is based on democratic models”, he said to Agência Pública.

On March 28 of that year, Garcia Alves, ALAI’s Brazil manager, signed a text proposing to keep Article 19 of the Marco Civil da Internet, which stipulates that digital platforms can only be held liable for third-party content if they fail to remove it after being ordered to do so by a judge. While the Court deliberated, ALAI organized a lunch for Brazilian authorities who were attending a forum organized by Gilmar Mendes, one of the Supreme Federal Court (STF) justices who voted on the case.

The Association, however, failed to achieve its goal, because in June the STF ruled that companies were responsible for harmful content even when there was no prior court order. Google, Meta, TikTok, and X were all involved in this legal process.

In Colombia, ALAI was part of a coalition of organizations that succeeded in getting Congress to amend a rule that sought to regulate digital content that could be hamrful to children’s mental health. (See full Colombia story), as recounted in another investigation by this journalistic alliance. Although civil society also criticized the initiative for granting excessive powers to the regulator, the arguments that carried the day in the Senate plenary were those of the tech lobby, which claimed the measure could threaten freedom of expression in Colombia and “lead to the arbitrary removal of information, limiting the diversity of opinions and voices in digital spaces.”

ALAI is also behind another influence initiative in the region: the Alliance for an Open Internet (AIA). This opposes the establishment of a so-called “network fee” — that is, requiring big tech companies to contribute financially to the operation of telecommunications infrastructure. The alliance began in Brazil in 2023 and its first executive director was former federal congressman Alessandro Molon (PSB – RJ). In 2025, with ALAI and several of its member companies as founding members, the initiative expanded to the rest of Latin America. Its regional director is Mercedes Aramendía, former head of Uruguay’s Regulatory Unit for Communications Services, a case that clearly illustrates the “revolving door,” by which companies seek to influence public power by hiring former government officials.

When asked about the selection of former public officials to fill management positions and for the reason for its expansion in Latin America, the AIA did not respond. The entity stated that it represents “more than 14,000 companies in Brazil” and that it “closely follows discussions on network tariffs and defends net neutrality as an essential principle for the Brazilian internet.” ALAI did not answer questions about its relationship with AIA.

Lobbying from Washington in Brazil

In addition to ALAI’s activities, Big Tech has also invested in regional influence operations through other international associations, such as the Information Technology Industry Council (ITI) and the Center for Information Policy Leadership (CIPL), both based in Washington, and Access Partnership, headquartered in London. In recent years, these organizations have focused on debates around technology company regulations, artificial intelligence (AI), and the network fee.

The ITI counts among its members Amazon, Apple, Google, Microsoft, Meta, OpenAI, Oracle, Lenovo, and NVIDIA. According to its website, the group seeks to ensure that “all governments around the world to develop policies, standards, and regulations that promote innovation and growth for the tech industry.” Founded in 1916, it has changed its membership over time with the evolution of technologies.

Between 2023 and 2024, ITI representatives held at least 11 meetings with members of Brazil’s Executive Branch, according to La Mano Invisible de las Big Tech, using data from the Transparent Agenda. They visited regulatory agencies, as well as ministries, and the Civil House of the Presidency of the Republic. At several of these meetings, ITI was accompanied by company representatives from Apple, Amazon, Meta, Microsoft, Mastercard, HP, IBM, and Intel.

According to one Brazilian public officer visited by the group, who asked not to be identified, ITI has been “very active” in the country since 2016. When asked about how these dialogues unfold with industry representatives, the official said: “the companies and associations usually arrive, sometimes they prepare a presentation, sometimes not, they introduce themselves, and then move on to a more specific topic to ‘show the absurdity of what is happening’ in a given matter. They knock on every door in search of the most receptive ear,” .

Agência Pública filed a Freedom of Information request for the minutes, notes, or recordings of the 11 meetings between ITI and Brazilian authorities. The Civil House stated that the meeting allowed ITI to present “points of attention” regarding Bill 2,338/2023, which proposes to regulate AI; the Ministry of Communications informed that the discussion focused on the implementation of communications infrastructure; and the National Telecommunications Agency, Anatel, reported they talked about cybersecurity requirements and regulatory best practices.

At most of the meetings with Brazilian authorities, the Brazilian lobbyist Husani Durans de Jesus was present. A former official of the country’s Foreign Ministry, he is now ITI’s Director for the Americas, based in Washington. Durans de Jesus travelled to Brazil at least three times in recent years, according to social media posts and Brazilian Congress entry logs: in March 2023, March 2024, and September 2024, sometimes accompanied by other members of the group.

The group also sponsored the seminar “Regulation of the Use of Telecommunications Networks” in Brasília, in partnership with Editora Globo, to discuss collection of the network fee. The association also signed four pieces of “branded content” on the financial news website Valor Econômico, as noted in the articles themselves.

In September, as the AI bill was being hotly debated in the Senate, Husani travelled to Brazil accompanied by Courtney Lang, another Senior Vice President of ITI, who leads the group’s global work on AI regulation. Together, they met with staff from Senator Eduardo Gomes (PL-TO), the bill’s author. “Fantastic meeting with Senator Eduardo Gomes’ office in Brazil,” Durans wrote in a social media post about the encounter.

A week before arriving in the country, Lang had already made very specific recommendations via videoconference during a public hearing on the bill. One of them was to eliminate two articles listing the rights of users of AI technologies, since they “assume there will be significant risks to human rights throughout the AI lifecycle, which, in my view, is not always the case.”

ITI has also hosted receptions for Brazilian lawmakers in Washington, such as in March 2024, according to LinkedIn posts and at least three travel reports filed by legislators. Among those present was Senator Marcos Pontes, who was member of a temporary Senate committee analysing the AI bill. From this committee he pushed for changes aligning the law more closely with Big Tech’s interests. He was the same senator who, months earlier, had invited Lang to testify at a public hearing on the very same bill.

In a statement, an ITI spokesperson said it interacts with government officials around the world “to promote policies and industry standards that advance competition and innovation on behalf of the technology sector”. Its engagements with Brazilian officials, the spokesperson said, focus on “enabling more citizens, businesses, and communities to benefit from increased digital connectivity and inclusion.”

Ponted did not answer to questions by Agência Pública about whether or not he believed there was any conflict of interest regarding his role in the committee.

During that same trip to the United States, Brazilian legislators also visited the Center for Information Policy Leadership (CIPL). According to its website, CIPL is a think tank that offers its members “opportunities to work on important issues related to privacy and information policy with key privacy experts and stakeholders from regulators, governments, and academia.” Its members include tech and telecom companies such as Amazon, Google, Microsoft, Tools for Humanity (Worldcoin), Telefónica, and Mercado Libre. Founded in 2001 by several companies and the law firm Hunton Andrews Kurth LLP (formerly Hunton & Williams), CIPL is another established lobbying vehicle.

The trip aimed to “guide decision-making and lawmaking related to AI in Brazil,” according to the event briefing accessed by Agência Pública. It was organized by the Competitive Brazil Movement, an organization seeking to foster closer ties between the public and private sectors.

In its 2024 activity report, CIPL celebrated that Brazilian legislators had incorporated into their AI bill several recommendations from a report it published on global AI regulation.

CIPL did not respond to questions sent by this journalistic alliance.

Other international lobbying firms are also seeking to influence Brazil’s legislation, given that it is one of the largest markets for the leading technology platforms. Paula Corte Real, a Brazilian lobbyist with the UK-based firm Access Partnership —itself as “the world’s leading tech consultancy” — has visited the Chamber of Deputies at least five times in 2025, according to a Freedom of Information request filed by Agência Pública. In the past year, Corte Real has met with lawmakers including Reginaldo Lopes (PT-MG), Helio Lopes (PL-RJ), and Lafayette de Andrada (Republicanos-MG), who chairs the Mixed Parliamentary Front for Digital Economy and Citizenship (the “Digital Front”).

In the Courts and in Congress

At times, the lobbying of these associations intertwines with the legal battles that tech companies wage against state regulators. In Brazil, the law firm Bialer Falsetti Associados (BFA), which defends Meta in data protection cases against the National Data Protection Authority (ANPD), counts attorney Ana Paula Bialer among its partners. Bialer took part in six meetings between ITI and Brazilian authorities, three of them at the ANPD offices.

She does not disclose her connection to ITI on her social media, but in the public agendas of Brazilian authorities and in records obtained by Agência Pública through freedom of information requests, she is identified as a consultant to the association.

Bialer is also an active lobbyist in the National Congress. She visited the Chamber of Deputies at least twelve times between 2023 and 2025, including on key voting days for major bills. On three of those occasions, she declared she was visiting the office of Deputy Luísa Canziani, president of the Special Committee on Artificial Intelligence in the Chamber of Deputies, who, as another story of this aliance reports, faces questions for possible conflict of interest related to Google. In 2021, the lawyer and the deputy co-authored an article defending an artificial intelligence regulation more favorable to the private sector, as revealed by Núcleo Jornalismo, a member of this journalistic alliance.

Regarding her dual role as lawyer and lobbyist, Bialer said she is a “professional with recognized experience in technology, privacy and data protection, cybersecurity, and artificial intelligence; and regularly participates as a speaker at public hearings, seminars, and panel discussions on the aforementioned topics.”

Bialer also said that BFA firm has been advising ITI in Brazil “for many years”, providing “legal and regulatory consulting services, as well as technical support in ITI’s discussions with policymakers in the country,” but did not offer further details and said that the activities are “subject to professional confidentiality obligations.”

The firm did not respond if it was representing Meta when it met with the ANPD on behalf of ITI, or whether it sees any conflict of interest in having its lawyers participate in meetings as consultants to the international association while also defending Meta in other proceedings.

Another case in which lobbying in Congress overlapped with litigation is that of Lorenzo Villegas Carrasquilla, a Colombian lawyer who since 2020 has represented Google in a lawsuit against the Superintendence of Industry and Commerce (SIC). In 2024, Villegas spoke at a public hearing on a bill that directly affected the tech giant, repeating the very same arguments the company had been making in Colombia’s courts.

In official rulings between 2019 and 2022, the SIC required Google, Meta, and TikTok to comply with Colombia’s regulations on protecting minors’ data, concluding that they were not doing so fully. But the companies sued the regulator before Colombia’s Highest Administrative Court (Consejo de Estado), arguing that the ruling violated their rights because the data processing does not take place in Colombia and therefore, they insisted, Colombian law does not apply to them.

The principle that companies must obey the laws of the countries where their users are located—regardless of where their headquarters are—is known as extraterritoriality. “This is telling companies, ‘even if you are not physically located in our territory, if you are collecting data from our citizens, you must comply with our legislation,’” explained Heidy Balanta, a lawyer specializing in personal data, to this alliance.

Colombian jurists consulted by this journalistic alliance expressed differing opinions on whether the regulator can enforce this principle. In any case, two bills would have resolved the matter had they not been shelved: Bill 156 of 2023 and Bill 152 of 2024. Both proposed that the handling of data collected in Colombia by a responsible party, or by its representative domiciled in Colombian territory, be subject to national data protection law—regardless of whether the data were processed in Colombia or abroad.

At the public hearing, attorney Villegas argued that the bill could affect press freedom—an argument echoed by several civil society representatives—as well as freedom of enterprise. He then raised another concern: the bill “is a disincentive to data processing, particularly in the digital world, from abroad toward Colombia.” He further claimed that the initiative “runs counter to the Political Constitution, which establishes that Colombian laws apply within Colombian territory, to those physically present within Colombian territory.” Villegas did not disclose in Congress his role on the Californian company’s legal team.

Villegas did not respond why he did not reveal his dual role. He said he was invited to the public hearing as a lawyer expert in technology law, and he agreed to attend because he believes “it is fundamental to offer technical and legal elements to enrich legislative debate.”

ALAI and other allies of the tech companies have taken the same line. A comment on the 2023 bill signed by Nieto, ALAI’s lobbyist, argued that “in a globalized world, where it is possible to provide services anywhere, to insist that all those [services] offered in Colombia must comply with these provisions is a disincentive for ensuring that a wide range of digital services remain available in Colombia.” And María Fernanda Quiñones, director of the Colombian Chamber of Electronic Commerce, said at the above-mentioned public hearing that “a rule with extraterritorial application undermines or discourages the country’s competitiveness.”

The concern for the tech companies is that such regulations create problems for managing and distributing their products internationally. “Big Tech doesn’t like extraterritoriality because it makes them subject to many different laws, and given their presence in so many countries, it creates a heavy compliance burden,” explained Viviana López, an attorney with the Transparency and Digital Rights program at Dejusticia, a think tank that promotes the rule of law in the Global South, to this alliance. “However, one could say the solution is simple: apply the highest protection standard in all countries.” Today, the European Union sets the highest data protection standard for its citizens and obliges tech companies to comply.

For data protection specialist Balanta, the consequence of countries like Colombia being unable to enforce their data protection laws is that Big Tech ends up treating Colombian users “as second-class citizens.” In her words, companies design their products to protect only those living in countries with strict privacy rules, while in other places “citizens often find themselves without recourse because the platform’s design doesn’t make it easy for them to exercise their rights.”

In Colombia, the bills that could resolve the issue are stalling in Congress, and in the courts, a ruling on whether the SIC overstepped in requiring the companies to obey Colombian law could still take years. “That litigation is endless,” said López.

In Brazil, meanwhile, social media platforms’ refusal to comply with national laws was among the arguments used by the Trump administration, this past July, to impose 50 percent tariffs on Brazilian exports to the United States. In its letter on the tariffs, the Trump government cited court rulings in which the Supreme Court had ordered platforms such as X and Facebook to suspend the accounts of people under investigation who had used them to call for a coup d’état, threaten judges, and spread disinformation. The US Trade Representative also launched an investigation “because of Brazil’s ongoing attacks on the digital business activities of U.S. companies.” The Trump decision was applauded by the Computer & Communications Industry Association (CCIA), funded by companies including Google, Meta, and Amazon, as revealed by Agência Pública.

Revolving Doors

Big Tech has also leaned on another strategy to get closer to authorities: hiring people who once held public office, a practice widely known as the revolving door. This journalistic alliance identified at least 59 such cases across Brazil, Canada, Colombia, Chile and Mexico.

In Brazil, the most notorious case involved former president Michel Temer, who was hired by Google in mid-June 2023 to bolster the company’s lobbying efforts in Congress and act as a “mediator” with lawmakers — as he himself confirmed to Folha de S. Paulo. At the time, Bill 2630/2020, known as the “fake news law,” was still under debate, with expectations it would soon be put to a vote, which never happened. (See full story).

In total, at least 54 lobbyists for tech companies who previously held public sector positions in Brazil, representing 68% of all the lobbyists tracked in the country, according to this investigation. For example, Sérgio Garcia Alves of ALAI himself once worked at Anatel, in the Casa Civil, and at the Ministry of Science, Technology and Innovation, before becoming the association’s public policy manager.

In Chile, lawyer Aisén Etcheverry was reprimanded by the Comptroller’s Office for joining a 2019 committee that ruled in favor of Amazon Web Services, where she had worked just months earlier. The sanction did little to slow her rise: she became Minister of Science, Technology, Knowledge, and Innovation in March 2023 and, from December 2024 to July 2025, also served as government spokesperson. Her case highlights how ties between officials and tech companies have helped these multinationals secure business.

“The decision that led to the ruling was the result of an open process, in which different proposals were received,” Etcheverry told this alliance. (See full story).

From Watchdog to Cheerleader in Colombia

On May 30, 2024, Worldcoin launched in Colombia. The service scans people’s irises in exchange for money, claiming that the process can “verify humanity” — in other words, provide users with a credential allowing digital services to confirm they are real people and not bots. Tools for Humanity (TfH), Worldcoin’s parent company, was founded by Sam Altman, who also co-founded OpenAI and is one of the most influential figures in the industry. TfH is banned in Brazil.

The very next day, the SIC Sierra — issued a brief press release on its website. The statement warned: “We invite citizens to carefully consider the potential consequences of granting this company access to their iris, since the firm in question has not demonstrated… that this practice does not involve the collection of sensitive personal data.” The regulator also announced an investigation into TfH to verify compliance with Colombian data protection laws. (The investigation was still ongoing as of September 2025).

Between February and December 2024, lawyer Grefieth Sietta was the delegate superintendent for personal data at the SIC. His office was in charge of the investigation. But on April 2, 2025, no longer at the SIC and now a professor at the Universidad del Rosario’s Law Faculty, Sierra said. “Strict privacy is not good business. We need to break the logics of privacy, because those logics of privacy are what is called monetization,”

He spoke at an academic event hosted at the university. He further argued that citizens themselves should decide how much of their privacy to cede to companies.

Speaking before Sierra was Lorena Buzón, Public Affairs Director at TfH. She began by thanking Professor Sierra “for conducting these discussions,” before claiming that the company’s product is in fact a “privacy-enhancing technology.”

In a LinkedIn post, Buzón wrote that Sierra had organized the conference. Yet no mention was made of past disputes: neither Sierra the host, nor anyone else, referred to the measures Sierra had once taken against Worldcoin in his role as regulator, nor to the concerns he had repeatedly expressed about the product. Nor did the event address the fact that Worldcoin has faced regulatory troubles in several other countries, precisely due to concerns over how it handles users’ personal data.

Sierra told this alliance that SIC’s investigation was not being conducted by him, but by the director of personal data investigations. Even though this official was his direct subordinate, he claims he never “assumed jurisdiction to investigate TfH.” He also said that the event was organized by the University, that his role was to perform “coordination tasks,” and that neither he nor the institution received any compensation for the conference.

Latam left behind

For users in Latin America, platforms like TikTok, WhatsApp messaging and other Meta’s social networks, YouTube, Google search, and cloud services from Google Cloud or Amazon are indispensable. They use them to talk, get information, store photos and documents, and express their views on the world. So when something goes wrong — for instance, when a young girl falls into the hands of a sexual predator she met in a group on social media — people want to know where to file a complaint and how to flag that dangerous account.

But many users have no idea how to get a platform to listen, how to lodge a complaint, or when they even have the right to do so. It isn’t easy even for well-established civil society organizations. In Colombia, Red Papaz has repeatedly tried to sit down with Big Tech to discuss how to prevent harm to children. “It’s like talking to a wall that tells you upfront it’s not going to do absolutely anything,” Alejandro Castañeda, head of the NGO’s Safe Internet Center, told CLIP and Cuestión Pública.

Nor are the platforms’ protection tools especially effective. In Colombia, a 2025 study by the Communications Regulatory Commission found that only 48% of parents use audiovisual content filters on platforms, and just 34% use parental controls on social networks. In Mexico, a 2022 report by the Federal Telecommunications Institute showed that only 26.2% of household internet users employ any parental control tools. And in the United States, platforms like Discord and Snapchat told Congress in 2024 that fewer than 1% of parents use these tools.

Even when people know these tools exist, there’s no guarantee they work. Initiatives like Circuito, run by the Linterna Verde organization, have documented such injustices. One Colombian cartoonist, falsely accused of spreading hate speech, lost his TikTok account for 10 years. A popular Mexican content creator was suspended from YouTube for posting a video about legal ways to emigrate to Canada. Users with connections or big followings sometimes manage to get such sanctions reversed, but many others don’t.

In much of Latin America, local offices don’t even exist. With some exceptions, issues in Ecuador and Peru are handled from Colombia; Uruguay, Chile, and Paraguay from Argentina; and Central America from Mexico. X, formerly Twitter, shut down all of its Latin American offices and now operates solely from the United States. Brazil, thanks to its market size and tougher regulatory push, is the outlier.

When it comes to financial reporting, many of these platforms don’t even break out revenues, expenses, and tax payments for Latin America, instead they lump them in with other regions.

As Castañeda from Red Papaz put it, Latin Americans’ use of digital platforms is “inequitable compared with the consumption that users in other countries are enjoying.” That inequity shows up not only in the tools available to them but also in the regulatory safeguards — stronger elsewhere, weaker here.

In Europe, meanwhile, the General Data Protection Regulation allowed citizens in 11 countries to sue Meta to prevent their information from being used to train the company’s artificial intelligence models. Meta was forced to stop and chose not to launch some AI products there.

By contrast, most Latin American users of Meta have no way to prevent the company from exploiting their data for AI training, as the organization Access Now has pointed out. “In most countries in the region there are no data protection laws, and in those where they do exist, they are outdated,” the group explained.

Once again, Brazil is the exception. In June, the National Data Protection Authority (ANPD) banned Meta from using Brazilians’ data for AI training. After complying with measures imposed by the ANPD — including not using children’s data and allowing users to opt out — the company resumed the practice with some restrictions. In December, the authority also prohibited X from using minors’ accounts to feed its AI.

This, despite the fact that a majority of people in the region support regulating Big Tech. An Ipsos survey found that “55% of people in Argentina, Brazil, Colombia, and Mexico favor AI regulation — and the proportion rises to 65% among those who say they have a good understanding of the tool.”

The absence of such rules elsewhere works to Big Tech’s advantage. As Alphabet, Google’s parent company, acknowledged in its 2024 annual filing with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission: “Our compliance with these laws and regulations may be onerous and could, individually or in the aggregate, increase our cost of doing business, make our products and services less useful, limit our ability to pursue certain business practices or offer certain products and services, cause us to change our business models and operations, affect our competitive position relative to our peers, and/or otherwise harm our business, reputation, financial condition, and operating results.”

The result is predictable: governments and regulators, hamstrung by weak legal frameworks, scarce resources, and often a limited grasp of complex technologies, face off against powerful corporations. The outcome is strong companies, weak regulation, and unprotected users. It is, as Andrés Hernández of Transparency International Colombia put it, “a completely unbalanced playing field.”

PayPal

PayPal