The first round of Brazil’s local elections took place on Sunday the 15th November and Damares Alves – minister for women, the family and human rights – has been in high demand on the campaign trail. With her popularity rising, she is seen Jair Bolsonaro’s trump card for the 2022 presidential elections and one of the favourites to become his running mate. Alves is the government’s main figurehead on moral issues, helping to shore up support from conservative voters.

While she has only rarely come out publicly in support of female candidates – “friends”, as she calls them in videos posted online –, since last year, Alves has been working behind the scenes to secure backing for more female candidates from political and religious leaders.

She has stated that she wants “at least one woman” in the council chambers of every Brazilian municipality (in the 2016 local elections, just 13% of those elected were women). She also launched a course to encourage women to run for office called “Marathon + Women in politics”. According to her ministry, it is a cross-party initiative without any religious criteria for participation, though it would not provide details on those who have signed up.

However, critics of the government argue that Alves’ aim is simply to get more female religious conservatives to participate in party politics. Indeed, this year’s local elections have the highest number of candidates who occupy some religious position since 2008. According to the Brazilian Electoral Court, amongst the candidates who identify as religious professionals – most of whom are from right-wing parties – 193 are women, as Pública revealed. Looking just at the registered names of the female candidates, the word “sister” appears 1159 times out of 186,144 candidates.

Success in a man’s world

“Damares mobilises the female evangelical vote,” says Jacqueline Teixeira, an anthropologist who studies issues of gender amongst evangelicals. For Teixeira, Alves’ success in conservative circles – traditionally a man’s world – have made her an inspiration for other conservative women, who have praised her on social networks and are replicating her political programme in their campaigning.

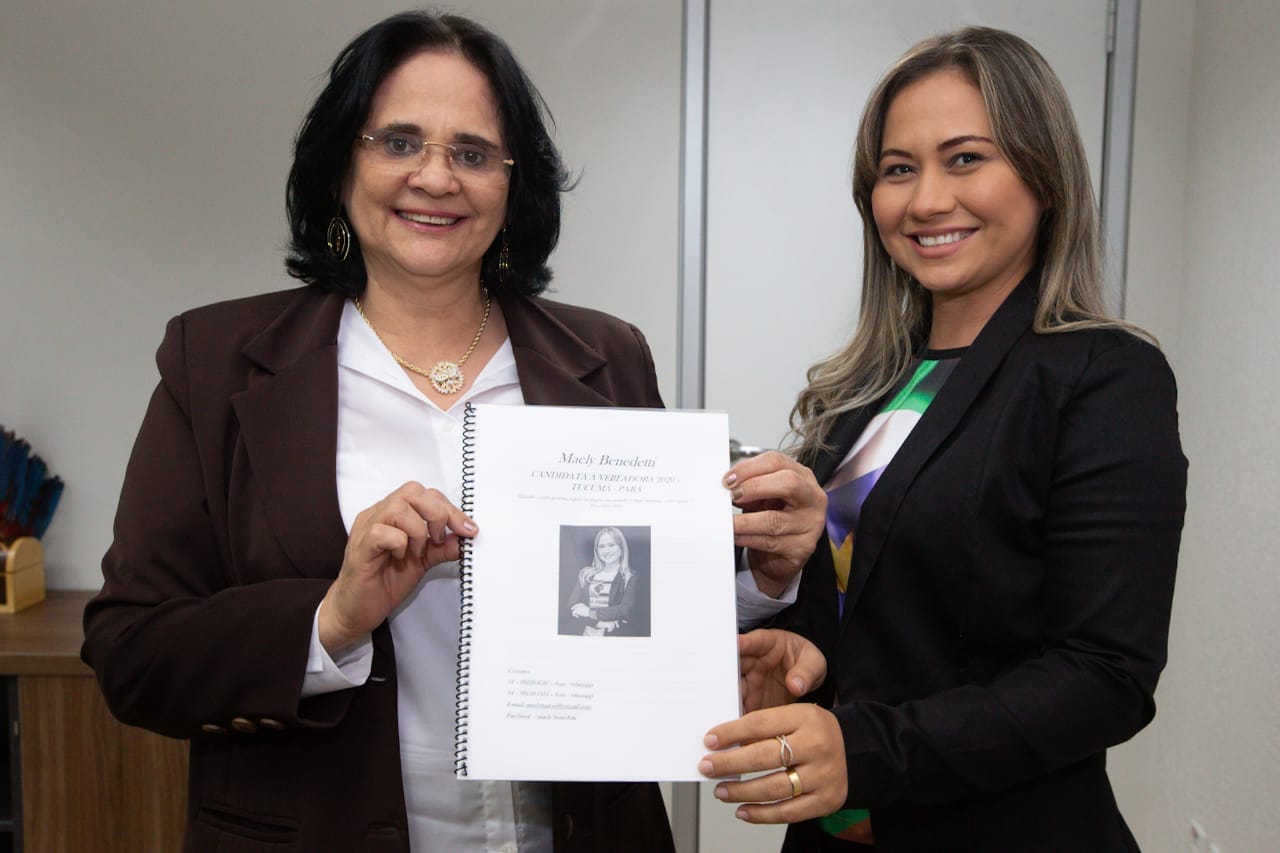

Alves’ endorsement has been used almost as a campaign slogan, as in the case of Maely Benedetti, elected on Sunday as a local councillor for Tucumã in the northern state of Pará. Alves featured heavily in Benedetti’s campaign material: she appears in a photo smiling and pointing at Benedetti, who responds with the same gesture. The text reads “Minister Damares’ complete support”.

Benedetti made her political debut just this year, defending “the family”, “equality” and “justice” in a successful social media campaign. On Facebook, she has a whole collection of photos in which she appears alongside Alves and has published attacks on feminism and “gender ideology”, a right-wing dog whistle which became widespread in the 2018 presidential elections and has been used to combat sex education in schools.

Alves sets the agenda

Alves’ main political priorities are child protection, defence of the heteronormative family and banning abortion – all pledges of conservative female candidates this year. Similarly, with her work on social projects, her career as a parliamentary adviser, and her evangelical religion, Alves has much in common with many of these candidates, who have emphasized this in their campaigns.

Alves has inspired Bruna Bahia, who ran for local council in Nilópolis, in the state of Rio de Janeiro – though ultimately she received just 26 votes. After losing two daughters in a car accident, in which she was also blinded in one eye, Bahia became an evangelical and founded a social project for women. “The minister is a woman of substance who fights for the things I believe in, like the family”, she told Pública in an interview.

A theology graduate, Bahia is 34 years old. She says she wakes up at 6am and after prayers and Bible study, sets to work sharing campaign material on WhatsApp and social networks. She believes that the Bolsonaro government was “chosen by God” and that conservative Christian women should participate more actively in politics to “bring an end to years of bad things done by people who aren’t Christian.” “We can’t be governed by politicians who try to destroy the family”, she argues.

The “aunts” protecting children

Thais Bertolete presents herself as “Protector of children, defender of the family.” But despite receiving explicit support from Alves, in the form of video Bertolete posted on her Facebook, she failed in her bid to become a local councillor in São Carlos, in the state of São Paulo, receiving just 184 votes.

“When God put this desire [to run for council] in my heart, I spoke to Damares. She knows about my work with children,” Bertolete told this report. She works at a children’s charity in the town.

Bertolete is not the only evangelical candidate for whom Alves has recorded a video of support. Rita Passos, who came second in the race to be mayor of Itu, also in São Paulo, posted a video very similar to that used by Bertolete, in which Alves calls her a “friend”, highlighting her work protecting women and children and combating domestic violence.

Alves also recorded a video in support of Emillye Malavasi, who ran for council in Votuporanga, again in São Paulo – though she received just 259 votes.

Better known as “Aunt Mi”, Malavasi is a Christian teacher who defines herself as an “antifeminist evangelist of children”. “I’m #Christian, #Conservative, I’m #Against #Gender #Ideology, I’m against #Abortion, #Defender of the #Family and #Childhood and #Antifeminist”, she wrote on Facebook. She also has a channel aimed at children on YouTube, where she teaches Biblical principles.

Malavasi has links to other candidates who present themselves as protectors of children – evangelical women who work with children in their churches, like Keyla Cristina, or Aunt Keyla, who ran for local council in Contagem, Minas Gerais. Again, she was unsuccessful, receiving less than 1% of the vote.

Tia Keyla, an educator specializing in the prevention of abuse and mistreatment, held a live webinar with Damares Alves on Facebook in September. Alves said she had been alongside Tia Keyla for a number of years “on a journey protecting children”.

‘In Brazil we have a team of aunts and uncles which holds events in churches at the weekends. During the week we travel all over the country, and at the weekends we meet each other at these events’, Alves said.

Against feminism and abortion

According to Teixeira, while evangelicals may employ a discourse of female empowerment, this often omits traditional feminist demands. “For many women, empowerment comes linked to a sense of belonging to a family, or perhaps to leadership of a religious group.”

Teixeira explains that amongst some evangelical groups, women may work and are not obliged to accept a relationship which is abusive or violent.

“The idea of submission to the man, of the man being the head of the family, as advocated in the Bible, doesn’t necessarily annul the woman. She sees herself as a leader in the family and in church. Many of them say that if the man is the head, they are the neck – the one who directs him. It’s a vision of empowerment distinct from that in feminist thought. Domestic violence is a concern, as is female participation in politics. They are seen as women’s issues, though they are also big concerns of feminism.”

For Teixeira, the distance from feminism is clearest when it comes to abortion. The fight against abortion is a major concern for Brazil’s religious community, uniting the fragmented evangelical scene and providing common ground with Catholic groups. It is also a priority for Alves and for most of the candidates interviewed by the report. Abortion law in Brazil is already strict, with the procedure legal only in cases of rape, anencephaly or when the woman’s life is in danger.

Promising to “transform Curitiba into Brazil’s pro-life capital”, Marisa Lobo – another Alves-backed evangelical – ran for mayor in Paraná’s capital, though she finished in ninth place, with just 2.2% of the vote.

Lobo was at Alves’ side during several battles against the decriminalization of abortion in Congress and was an aide to the Evangelical Parliamentary Front whilst Alves was working for the former senator Magno Malta. “We worked behind the scenes,” Lobo said of herself and Alves in an interview with Pública. “We helped congresspeople and candidates. But now we’re on the front line.”

And in 2014, Lobo, a Christian psychologist, had her licence revoked by the Paraná Regional Psychology Council, accused of promoting the so-called “gay cure” – also known as conversion therapy –, which is prohibited in Brazil by mental health authorities. At her hearing, Lobo was represented by none other than Damares Alves, who worked as a lawyer before she entered government. Alves got the decision reversed.

Teixeira, however, warns against stereotyping. “It would be a mistake to consider all evangelical women reactionary.” She emphasizes that there are many nuances within the Brazilian evangelical community and that it is impossible to generalise either the thought or behaviour of its members.

But Nina Rosas, a professor of sociology and researcher of religion at the Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, points out that politically, Brazil’s evangelical community is largely represented by conservatives opposed to abortion and discussion of gender issues. This is reflected clearly by the activity of Bolsonaro’s ministers, particularly Alves, and by the Evangelical Caucus (a loosely organised but influential group of evangelical representatives) in Congress.

For Rosas, this means that female evangelical candidates almost always define themselves in terms of empathy and obedience, which may ultimately have a negative impact on female political representation.

“When a woman runs for office it’s seen as a religious mission, a family project, often with much interference by the husband in what she does. So while on the one hand, there is a movement towards getting women out of the domestic sphere, the very discourse of these women is reaffirmation of patriarchal values,” she argues.

But regardless of the ideology or beliefs of the candidate, Rosas emphasizes that “having fought for it, women have the right to a place in politics.”

PayPal

PayPal