In May 1971, Dênis Casemiro, a 28-year-old Brazilian mason and member of the armed group VPR (Popular Revolutionary Vanguard), died under torture at the hands of agents from the Department of Social and Political Order (DOPS). His remains were the first identified after the discovery of a clandestine mass grave at Perus Cemetery in September 1990. This event had significant implications for the Brazilian state and Casemiro’s family. A dignified burial took place on August 13, 1991, in Votuporanga, São Paulo, the homeland of the Casemiro family, nearly 20 years after his death.

The identification made 34 years ago by coroners from the University of Campinas (Unicamp) was, however, incorrect. It was finally rectified this April 16 thanks to a series of new examinations conducted by the Perus Project, a partnership between the Ministry of Human Rights and Citizenship, the Federal University of São Paulo (Unifesp), and São Paulo’s City Hall, led by the Center of Forensic Anthropology and Archeology (CAAF/Unifesp) and the Special Commission on the Political Dead and Disappeared (CEMDP).

At the CAAF, the remains that were confirmed as being Dênis Casemiro’s were submitted for three different types of analysis, including a genetic identification, where DNA is extracted from the remains and compared with other genetic material collected from first-degree relatives of the person who died.

This work was coordinated by Professor Edson Teles, who resumed the identification of remains found in the Perus mass grave after this work was nearly paralyzed and the special commission was disbanded during Jair Bolsonaro’s government (2019–2022). President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva recreated the commission and resumed identifications in 2024.

The mass grave in Perus contained 1,092 bones, with experts estimating that at least 42 politically disappeared were buried there. Project organizers collected genetic data from 34 families. According to the federal regional attorney Eugênia Augusta Gonzaga, president of the commission, the comparison work with the available material is 80 percent concluded. In the most recent instance, some bones from Perus were compared to DNA samples from the Casemiro family, showing a 100 percent match.

“Our luck was that there was an open lawsuit [on this case], with a judge and a prosecutor following it. The Ministry of Human Rights agreed to go on with this exhumation [of the bones thought to belong to Dênis Casemiro],” Gonzaga told Agência Pública. The suit was filed with the consent of his family.

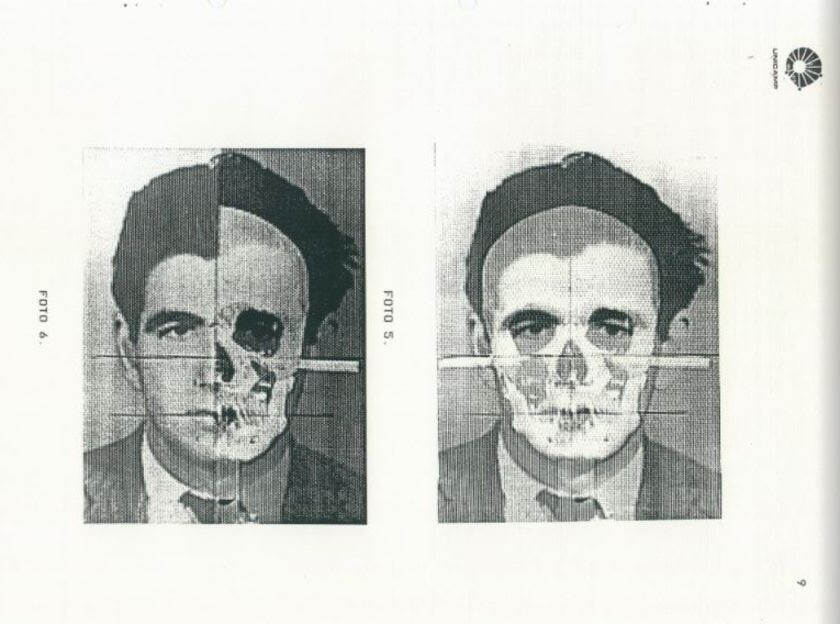

Casemiro’s remains were exhumed because, when the previous identification was made in 1991, Brazilian authorities didn’t have access to DNA testing technology. Back then, a picture of him was superimposed over a skull found at the time. His brother, Dimas Casemiro, who was killed by the dictatorship a month before him, in April 1971, was also buried at the same graveyard in Votuporanga. Dimas’ identification took place in 2018, when DNA testing was already available.

When the bones that were attributed to Denis were compared to Casemiro’s family’s DNA, researchers concluded that the remains buried in 1991 weren’t his.

The remains that were buried as Dênis Casemiro over three decades ago are now part of the archive of the Perus Project, and so far haven’t been matched with any DNA samples currently available in the genetic database.

The recent identification of Dênis Casemiro and another individual, Grenaldo de Jesus da Silva, marks the first positive result among victims found in the mass grave in Perus since 2018. Silva was murdered at 31, in 1972, while he hijacked an airplane at Congonhas airport in an attempt to flee the country.

Counting Casemiro and Silva’s identifications, there are now six political militants recognized among the remains found in the Perus mass grave. The official announcement, made on April 16, 2025, happened three weeks after the Brazilian state apologized for negligence in identifying the remains found at the site.

Nevertheless, to Edson Teles, the mistake was not the result of negligence, but of technical limitation. “Today we have access to genetic comparison between the DNA from relatives and the bone material, which allows us to be more certain of the final result and enables the revision of the results,” the CAAF coordinator said during an interview with Pública.

According to Gonzaga, the president of the Special Commission on the Political Dead and Disappeared, both Casemiro and Silva’s families have been informed about the matches.

False reports and burials at Perus

Both men identified now, Dênis Casemiro and Grenaldo de Jesus da Silva, were killed by state agents, and had their death reports falsified at the Legal Medical Department (IML, in Brazil). They were buried anonymously in Perus, even as those responsible for their deaths knew who they were.

According to the Commission on the Disappeared and the National Truth Commission, which reported on the crimes committed during the dictatorship, Casemiro was detained in April 1971 by a Department of Social and Political Order (DOPS) team. He was tortured for a month at a police station in São Paulo and didn’t survive the violence he suffered.

Documents from DOPS indicate that Casemiro was shot while trying to escape from prison and was found hospitalized in Ubatuba, a city on the shore of São Paulo, the following day. He was taken by the agents to a hospital and, allegedly, died on the way. The Legal Medical Department’s report corroborates this version, but ignores the torture marks all over his body.

Grenaldo de Jesus Silva joined the Navy in 1960, at 18 years old, and became a member of the Sailors and Marines Association of Brazil (AMFNB), an organization fighting for better wages for sailors, soldiers, and corporals in the force. The movement was declared illegal right after the 1964 coup d’état, and Silva was one of 414 marines arrested. He managed to escape from prison and started to live undercover in São Paulo.

On May 30, 1972, Silva told his wife he didn’t feel safe living clandestinely, wrote a letter revealing his situation, and hijacked a Varig aircraft at Congonhas airport. The plane was surrounded by police officers who tried to negotiate with him. Silva released the passengers and, according to the official version, when he realized he wouldn’t be able to flee, he killed himself with a shot in the head.

Reports maintained this version until 2003, when Epoca magazine found the flight controller on duty during the hijacking and a Varig mechanic who was onboard the plane. The controller said Silva carried a letter on his shirt, saying he was going to Uruguay, since he couldn’t find a job due to the lack of documents, and that later on, he would come for his wife and son.

The flight mechanic said he was forced to confirm the suicide version and that the fatal shot suffered by Silva was to the back of his head.

PayPal

PayPal