Things have changed in the last decade for 42-years-old Antonio Martínez. Beneath his feet, the fields are drying up. In his village, blackouts have begun, leaving them without power for hours. And their homes are increasingly surrounded by large industrial parks that rise up as a new business, unknown until just a few years ago, arrives: data centers. Martínez is one of the last farmers in Viborillas, El Marqués, a small community of barely 1,500 people in the Mexican state of Querétaro.

Everything Antonio Martínez knew as a child—the cornfields and milpa plantations, the wells with water for the crops, the fields that stretched as far as he could see—has become the promised land for tech giants.

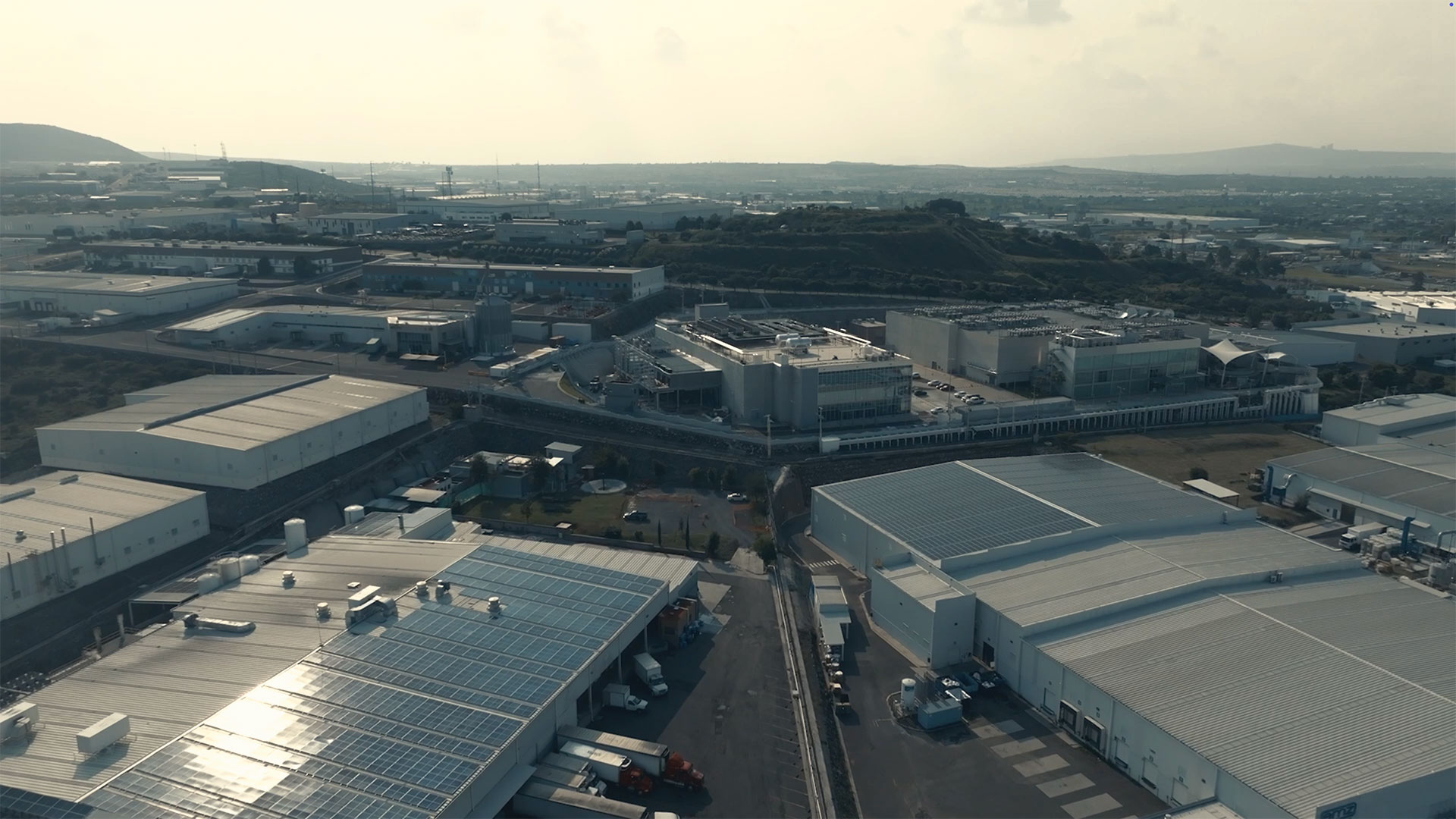

Since 2020, large companies like Microsoft, Amazon, and Google, as well as lesser-known ones like Ascenty and Equinix, have established themselves in the state, a three-hour drive away from Mexico City. Their main destinations were Colón and El Marqués, two small municipalities located near the international airport, almost adjacent to the state capital, also named Querétaro.

There they found what they were looking for: a stable terrain, free of earthquakes, and good connectivity. Also, and more importantly, a government that rolled out the red carpet: laws adapted to the needs of businesses, practically free land, and easy access to natural resources that residents are short on, such as water and energy.

Antonio Martínez has lived his entire life there. He has had to see how a community devoted to agriculture became entrapped in a new industry, that turned into a behemoth with the rise of artificial intelligence.

No one has explained him what these infrastructures —that governments have embraced gleefully— are for.

“I imagine it’s where they store data, whether it’s phone calls, company data, or even government data. I imagine that’s what it is,” he says, while walking through a barren field.

The arrival of data centers in Querétaro has been portrayed as a major economic opportunity. There is political consensus around their arrival. The federal government, led by the left-wing party Morena, and the state government, led by the right-wing PAN, are on the same page: the big tech giants will bring investment, economic growth, and jobs. These are the figures the industry claims: USD 18 billion in direct investment; USD 27 billion in indirect investment; and 100,000 new jobs, 20,000 of which will be directly created by the industry.

Adriana Rivera, director of the Mexican Data Center Association, says there will be 100 data centers across the country by 2030, at least half of them located in state, and the central region of the country.

The current figures are lower. The industry expects to increase tenfold over the next five years.

The Querétaro government’s Sustainable Development Secretariat has awarded 20 permits, almost all in Colón and El Marqués.

The trade association says there are 34 data centers: 14 in Querétaro, 10 in the Metropolitan Area, 4 in Nuevo León, 3 in Jalisco, and 2 in Yucatán.

Currently, these data centers have a combined maximum capacity of 250 megawatts.

This metric is key to understanding how the business operates. The centers are not measured by their storage capacity, but by how much energy they consume.

The growth forecasts, however, are enormous.

“For example, the capital of Querétaro consumes approximately 2 gigawatts to operate its medical services, electrical services, lighting services… And the city—the houses, the housing, the schools—all of this requires about 2 gigawatts. If we require 1.5 gigawatts, that’s a lot, right?”, says Rivera.

This boom has a direct impact on the electrical system.

Documents from the National Energy Control Center (Cenace) alerted in 2023 that peak energy demand, combined with new requests, exceeds installed capacity, jeopardizing the capacity of ensuring a reliable electrical supply.

The same report warns that data centers might overload Querétaro’s electrical grid.

“Given the expected demand conditions on the Querétaro electrical grid, the requests for Load Centers with Priority and under study, as well as the maximum capacity of the data centers in the regions of Querétaro, San Juan del Río, and San Luis de la Paz by 2028, and considering the already commissioned projects and reinforcement works, overloads are expected on the 115KV electrical grid,” the report states.

Querétaro is already enduring the impact. Cenace recorded more than 300 power outages across the country between 2021 and 2023, most of them in Querétaro and Guanajuato.

N+ has reported blackouts and power outages since at least 2023.

In Viborillas, the community of Antonio Martínez, the power went out at least three times last August, leaving residents without power for several hours.

“We don’t know what’s going on. They haven’t told us what’s happening with the power outages we’ve had. Before, a year or two years ago, we didn’t have any power issues. Now, it’s been twice a week. And they are long; can be 4 hours, 5 hours, even a full day,” says Ana Ceferino, a 46-year-old woman who runs a small shop on one of the main streets.

The woman has lived in the community her entire life and says the power outages are affecting both her business and her home. She also says other neighbors have had to purchase generators.

Adriana Rivera acknowledges the issues. “Querétaro is a city that has grown because the industry has created specialized jobs. So, it’s obvious that the electrical grid also must grow. But if in seven years you don’t invest anything to expand it, modernize it, or maintain it, as has been the case so far, then obviously this could lead to outages,” she says. She says, however, that both the federal government and the industry are planning investments to alleviate these failures.

The Cenace report, in fact, claims there are plans to spend 3 billion pesos (USD 162,4 million) by 2028 to prevent system overload.

The industry claims that 35% of its investment will be to improve the electrical grid. However, it does not provide data on how many projects it has financed.

Reports obtained by N+Focus indicate that tech giants are also affected by power issues. At least five data centers have either not started operations or have been halted due to a lack of connectivity.

Faced with the lack of capacity, companies like Microsoft have turned to their own gas generators while they are able to connect to the Federal Energy Commission (CFE) grid. A combined-cycle power plant in Querétaro was scheduled to come online this year to help generate more energy. But this, in turn, will increase emissions and contribute to climate change. In a statement sent by Ascenty to this journalistic alliance, the company contends that the claim that “the installation of new data centers in Querétaro, including those built by Ascenty, has motivated the construction of a new fossil fuel power plant, is unfounded.”

In other parts of the world, tech giants turned to other types of energy.

This is explained by Benjamín Agullón, a former public official and current entrepreneur who is responsible for connecting data center companies with public administrations.

“I think it was AWS, Amazon Web Services, that said, ‘I’ll either start up this energy, this nuclear power plant, on the condition that it’s used for my data center.’ So, we need to open our eyes and see what other energy sources could already be used, and also destigmatize certain energies, such as nuclear energy, to evaluate their viability,” he argues.

Ramsés Pech, an economist and energy expert, says performance will depend on the kind of plant where the energy comes from. “They will require a lot of energy. A solar or wind plant can work when batteries exist. Many will turn to combined-cycle plants or nuclear power; this is already happening in the United States and China,” he says.

Power overload is one of the downsides of data center growth. Another much more visible issue is the impact on the water supply. Particularly in a state like Querétaro, where 17 of 18 municipalities suffer from drought. This is a controversial point. Some activists denounce data centers consume too much water. The industry argues that technology has evolved and that there is currently no direct relationship between its activities and the lack of water.

Querétaro has been suffering from water stress for at least a decade.

“In the last 10 years, the lack of water has decreased our yield by roughly a 50%,” says farmer Antonio Martínez.

He speaks as someone who has dedicated his life to farming.

“This used to be an irrigated land. There was a well here, but it’s dried up some five or six years ago. What condition are the milpas in? There’s no water, and without water, we can’t plant. Without water, the plots don’t produce anything,” he complains.

Climate change has hit Querétaro hard, as it has across Mexico. In 2022, its industrial corridor recorded a 1.6-degree increase compared to its historical average and 40% less rainfall.

Water bodies have been wearing out for years.

In 2015, Conagua, the federal agency that regulates the nation’s water system, warned that four aquifers in the area were experiencing water shortages and recommended against granting further licenses. At that time, Marco Antonio Del Prete took over as the state’s Secretary of Sustainable Development and launched a strategy to attract tech giants. Companies began to arrive and multiply. Del Prete himself highlighted the role of the state government in facilitating investments in data centers on Data Cloud 2024, an event held in Austin, Texas.

They found two ways to obtain water. The first was to purchase a portion of the already issued permits. This is a common method by which a private individual with a water extraction license sells part of these rights to another interested party.

The second is to rely on the state government, eager to make things easier for Bill Gates’ or Jeff Bezos’s envoys by directly supplying them with water.

The Brazilian company Ascenty, owner of three plants in Querétaro and provides services to Microsoft on two of them, achieved just that.

N+ Focus obtained the request the company filed for potable water services for its third data center, which is not yet operational. The permit was issued in May 2023. The Querétaro government guaranteed a maximum of one million liters of water per month. But the company argues that it spends much less, stating that the water it draws from public facilities is for human consumption only.

A new law allows this tactic since 2022, when the current governor, Mauricio Kuri, promoted a new water regulation known as the “Kuri Law”. This law, which was opposed by social and environmental organizations, allows municipalities and the state water agency to grant concessions —something that was previously solely within the jurisdiction of Conagua. At least seven of the data centers installed in Querétaro requested permits a year earlier, in 2021.

The other way companies are obtaining water amid the shortage is by extracting it from already-authorized wells. Microsoft does that in the Vesta industrial park, where it has a license to extract 25 million liters per year starting in 2023, according to documents from Conagua obtained by N+Focus. The company was transferred part of an extraction permit owned by QVC, a corporation linked to the Vesta industrial park, where Microsoft’s data center is located.

Ascenty also has a legal permit since 2020 to extract water from a well that belongs to Conagua, as was made public when it purchased the plot of land where it established its second data center from a company linked to the University of Arkansas. According to the document, the Brazilian company can extract up to 60 million liters in total, at a rate of 3.5 million liters annually.

That water, according to Arturo Bravo, general manager of Ascenty in Mexico, is limited to “human consumption.”

In several countries, like Chile and Spain, there have been protests over data centers’ excessive water use. In Mexico there has been no organized groups or demonstrations, as there is little information on how much water companies use, or what they use it for. In Querétaro, however, a protest movement has emerged against water scarcity and its privatization triggered by the so-called “Kuri Law.”

There is controversy over the real impact of data centers on water scarcity.

Some experts claim that the internal processes for cooling server chips within data centers force companies to use significant amounts of liquid. Eugenio Tisselli, a programmer and researcher who is critical of new infrastructures, explains that “we’ve all experienced it at home when we have the computer running and it heats up if we’re performing a very complex process. If the processor gets too hot, it can stop working. In a data center, one of the most important issues is a continuous supply of data. Therefore, computers must be constantly cooled,” he says.

The authorities and the industry are on the other side of the issue.

Del Prete, the local Secretary of Sustainable Development, is one of the main advocates for the arrival of data centers. He has participated in international forums defending Querétaro’s role as a hub for the industry and asserts that technology has advanced enough to limit its impact on the environment.

“I think the issue of water consumption is a poorly told story,” he says. “Before, cooling a building required a lot of natural resources. To cool the building, you need to have water constantly circulating. So, there was indiscriminate water consumption. However, cooling technology has evolved,” he says.

The companies keep their internal operations secret and leave few records. N+ Focus inquired about operating details to several companies but received no response, except from Ascenty, that allowed a visit to its facilities. However, it obtained access through transparency requests to three environmental impact statements submitted by two companies, that reveal some key data. One of them comes from Alestra in 2013, and the other two were submitted by Ascenty in 2020 and 2023.

Alestra’s is a small infrastructure of barely 11 MW at its maximum capacity. It’s important to keep in mind that at that time, more than a decade ago, the streaming boom hadn’t occurred, the digitalization of public administrations hadn’t yet occurred, and artificial intelligence was barely a science fiction idea.

According to this document, Alestra planned to consume a maximum of 3.5 million liters of water per month, which it would extract from the permit for industrial park where it was located. The company’s investment is $4 million and it expected to create 58 jobs when it became operational.

In 2020, Alestra was acquired by Equinix, another giant in the sector.

The second environmental impact statement is more sophisticated, as it concerns centers considered hyperscale — meaning they have the capacity to support current demand, such as AI or video streaming. In this case, no reference is made to their megawatt capacity. The documents only say the data centers will be connected to the CFE grid — but Arturo Bravo, CEO of Ascenty, said the maximum capacity of the company’s three data centers in Queretaro is 20, 35, and 20 megawatts.

The document does not estimate their water consumption. The company stated that each one of its two operating data centers uses 1.7 million liters per year.

The planned investment for the first plant was of $60 million, and it forecasted the opening of 300 jobs during the construction period and of another 100 permanent jobs once operational. There is no similar information on the second one.

In both cases, Ascenty indicates that it will use the cooling system known as the Chilled Water Plant, which uses “large containers of water” that circulate between the systems to prevent them from overheating.

Arturo Bravo explained that this system is closed and does not suffer from evaporation. He said that 200,000 liters of water were injected at the start of the operation, which will continue to circulate throughout the data center’s operation.

He acknowledges that there are other systems, known as “cooling towers,” that do involve significant water consumption. According to the Mexican Data Center Association, only 2% of its infrastructure uses this equipment.

Secretary Del Prete insists that the impact on water stress is not a problem.

“If data centers required as much water as they say they do, they wouldn’t be based in Querétaro. We wouldn’t have enough water to satisfy them. Querétaro’s water is for the citizens, for the families,” he says.

The reality is that almost 15% of Querétaro households lack piped water, and outages are frequent in two out of every ten homes in the state, according to data from the National Institute of Statistics and Geography (INEGI).

Sandra García, a resident of Viborillas who has lived in the community for three years, must deal with the frequent shortages. “It’s been two months now without a drop of rain,” she said in an interview conducted in May 2025. She says her landlord only has access to water once a week, so she is forced to collect it when they notify her and store it for personal hygiene and washing dishes.

“There’s no information,” complains Elizabeth Duran, a member of the collective Voceras de la Madre Tierra, which denounces environmental harm in Querétaro. She says state reports claim the 19 data centers installed there consume the same amount of energy as 506 households, on average. “You’re telling me the problem is me showering or wasting water, when the problem is that you’re issuing permits for the installation of data centers,” she argues.

The industry denies responsibility for these events.

“These water shortages, which I don’t know if they’re actually happening near the communities where we’re located, are not because the industry is consuming water for a production process, or for a cooling process. That’s a lie. That’s speculation,” says Adriana Rivera.

Companies do not provide individualized data for each plant. The closest information available is an internal report from the Mexican Association of Data Centers, which indicates that current consumption for all data centers amounts to approximately 850,000 liters per month.

“The government headed by Mauricio Kuri is a pro-business government that seeks to promote growth and the development of citizens through investment and employment.” With this statement of intent, Marco Antonio Del Prete explains his position on the large North American companies that have arrived in his territory. He says the way to attract them has not been through tax exemptions or land grants, but rather by providing them with “talent.”

For years, there have been constant public meetings between companies and representatives of the federal and state governments. Public officials are also frequent guests in events sponsored by companies or by civil associations linked to them.

For example, investments from companies like Amazon are included in Plan Mexico, the program through which the federal government presents proposals for long-term economic growth. In fact, its representatives promised a $5 billion investment during a press conference held at the National Palace on January 14, 2025.

To the date, there is no specific legislation on data centers. However, the sector is preparing to participate in the public debate. Amet Novillo, president of the Mexican Association of Data Centers, urged his members to work to influence the legislative framework during the group’s anniversary meeting held in Querétaro in May 2025.

“It’s not just about doing business, it’s about networking and making things happen. I want to ask for your participation, please. We have a lot of work to do on the regulatory front,” said the executive.

Big Tech companies have been pursuing the federal government’s complicity for years. Amazon, Google, and Microsoft all signed collaboration agreements with the Ministry of Economy between 2020 and 2021. According to Adriana Rivera, this agency is a strong “ally” of the sector.

This doesn’t mean they haven’t received any benefits. For example, adapting regulations to the companies’ needs or providing land for them to establish themselves.

One of the mechanisms used by the state government to encourage the arrival of companies was an exemption from the obligation of issuing an environmental impact statement — the document in which companies explain their projects’ potential environmental harms.

Microsoft, Equinix and Amazon have taken advantage of this exemption.

In 2014, Alestra had to submit its documentation, even though it was located in a technology park. Now, after 2021, large North American companies were spared, under the argument that the park’s infrastructure had already legalized their status. Documents reviewed by N+Focus, however, prove that on at least two occasions, a company did not have to submit its internal data simply because it was a “data center developer.”

This allows large technology companies to conceal how much water they will actually use, what their projected energy costs are, or how many jobs each plant creates.

Another benefit granted to some companies was the donation of land. This was the case in 2024 with Cloud HQ, which received 50 hectares through the creation of a trust between the private company and the Querétaro government, in which it contributed just 1,000 pesos (USD 54).

The corporation’s promise: to invest 70 billion pesos (USD 3.8 billion) and create nearly 2,000 jobs.

But here in Colón or El Marqués, almost no one knows what data centers are, how much they cost, or how this affects the environment.

Still, some companies did try to foster good will among the residents.

In 2020, Microsoft made visits to eight communities as part of a program developed in partnership with UN Habitat.

According to a document from the program, “the project aims to develop participatory planning processes in the territories where new data centers will be built, in order to develop recommendations and an action plan to make communities more prosperous, sustainable, inclusive, and resilient.”

Microsoft and UN-Habitat acknowledged drought is one of the area’s bigger problems. They also proposed an investment of more than 80 million pesos (USD 4.3 million) for improvements in eight communities affected by the data centers.

These projects were never carried out, as N+Focus was able to verify after visiting several communities and speaking with authorities. However, the document never set a deadline or made an explicit commitment to the investment.

UN-Habitat said it was unaware of the project’s progress since it was delivered and had no further information on the matter.

The rise of artificial intelligence has multiplied the growth of data centers around the world. In Mexico, tech giants set up shop in Querétaro with the support of the federal and state governments and the promise of major investments and more jobs. Meanwhile, in the communities, the drought worsened and power outages increased. Wealth did not reach everyone equally in the promised land of data centers.

Big Tech’s Invisible Hand is a cross-border, collaborative journalistic investigation led by Brazilian news organization Agência Pública and the Centro Latinoamericano de Investigación Periodística (CLIP), together with Crikey (Australia), Cuestión Pública (Colombia), Daily Maverick (South Africa), El Diario AR (Argentina), El Surti (Paraguay), Factum (El Salvador), ICL (Brazil), Investigative Journalism Foundation – IJF (Canada), LaBot (Chile), LightHouse Reports (International), N+Focus (Mexico), Núcleo (Brazil), Primicias (Ecuador), Tech Policy Press (USA), and Tempo (Indonesia). Reporters Without Borders and the legal team El Veinte supported the project, and La Fábrica Memética designed the visual identity.

PayPal

PayPal