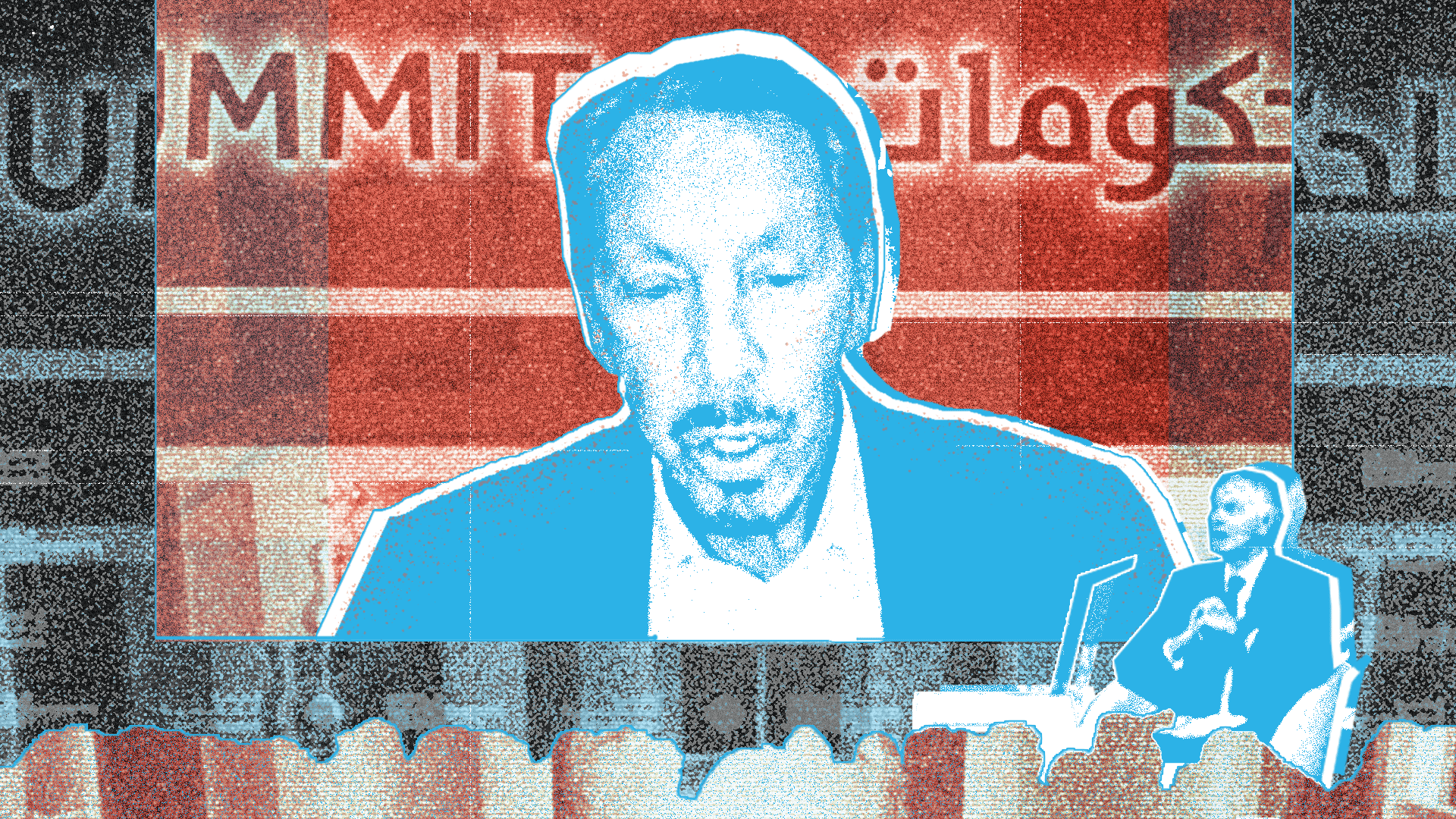

Tony Blair has rarely looked smaller. Seated alone on a vast Dubai stage in February with ranks of premiers and ministers filling the auditorium at the World Governments Summit, he sounded hoarse as he introduced his patron. Looming over him on a giant screen was Larry Ellison, founder of Oracle, whose share price this month briefly made him the richest man in the world.

After a joke about his good friend Elon Musk, Ellison warned the audience that artificial super intelligence was coming sooner than anyone expected. What, Blair asked him, should governments everywhere be doing?

“The first thing a country needs to do is unify all of their data so that it can be consumed and used by the AI model,” Ellison responded.

When his first biography appeared, it was titled: “The Difference Between God and Larry Ellison: God Doesn’t Think He’s Larry Ellison”

Now 81 years old, Ellison’s trademark pencil beard is unchanged from the 2003 cover photo. The billionaire used “we” to refer to all advances in AI. But neither man mentioned the $130 million Ellison’s personal foundation invested between 2021 and 2023 in the Tony Blair Institute for Global Change (TBI) nor the $218 million pledged since then.

The owner of super yachts, two fighter jets, and a Hawaiian island, was specific about which data needed unifying and he had an example in mind: “The NHS in the UK has an incredible amount of population data,” he enthused, but it was “fragmented”. Down below him, Blair nodded, clutching his TBI embossed notebook.

Two weeks later, Blair’s institute published a report entitled Governing in the Age of AI: Building Britain’s National Data Library. In it, the not-for-profit institute echoed Ellison on the UK’s data infrastructure, calling it “fragmented and unfit for purpose”.

Privately, TBI has lobbied ministers on technology and had policy proposals taken up by government. Critics say that was part of a major influence operation that could yet culminate in US tech firms taking control of Britain’s most valuable data.

TBI is unlike any other UK think tank. Ellison donations have seen it grow to close to 1,000 staff, working in at least 45 countries. It enjoys US levels of funding and influence, so while UK counterparts like Policy Exchange had income of £4.3 million in the last financial year, and the Institute of Public Policy Research registered £4.3 million in 2023, TBI’s turnover was $145.3 million. The institute has insisted that Ellison is just one among many major funders and his chief policy strategist, Benedict Macon-Cooney told media that there was “no conflict of interest, and donations are ringfenced”.

TBI is unlike any other UK think tank. Ellison donations have seen it grow to close to 1,000 staff, working in at least 45 countries. It enjoys US levels of funding and influence, so while UK counterparts like Policy Exchange had income of £4.3 million in the last financial year, and the Institute of Public Policy Research registered £4.3 million in 2023, TBI’s turnover was $145.3 million. The institute has insisted that Ellison is just one among many major funders and his chief policy strategist Benedict Macon-Cooney told media that there was “no conflict of interest, and donations are ringfenced”.

Blair himself takes no salary from TBI but in recent years it has been able to recruit from bluechip firms like McKinsey and Silicon Valley giants Meta. In 2018 before the Oracle founder’s funding surge, TBI’s best-paid director earned $400,000. In 2023, the last year where accounts are available, the top earner took home $1.26 million.

One former staff member said the effect of this cash injection was to make the culture “toxic as fuck”, while others described a form of AI boosterism that silenced nuance and pushed the boundaries of lobbying for Oracle. Some TBI staff — including a number who left because of it — say the cash injection has produced a toxic culture at the institute that is rife with nepotism , dominated by AI optimism that silences nuance and pushes the boundaries of lobbying for Oracle.

Investigative newsrooms Lighthouse Reports and Democracy for Sale interviewed 29 current and former TBI staff most on condition of anonymity. Supported by public documents and those obtained under freedom of information laws, the testimony describes an organisation unusually close to the British government that holds joint retreats with Oracle and is willing to engage in “tech sales” with governments in the rest of the world – sometimes to the potential detriment of local populations – under the guise of consultancy.

“When it comes to tech policy,” said a former senior advisor in the UK. “TBI’s role is to go to developing economies and sell them Larry Ellison’s gear. Oracle and TBI are inseparable.

A TBI spokesperson said: “TBI and Oracle are two separate entities. We collaborate with Oracle to help the work we do in supporting some of the poorest countries in the world, and we are proud of this. […] TBI does not advocate for Oracle’s commercial interests, nor does it advocate for any tech provider.”

Oracle declined to comment when contacted about this article. The Larry Ellison Foundation did not respond to a request for comment.

Land of hope and data

Ellison and Blair’s relationship began as it continues, with the Chicago-raised entrepreneur making charitable donations and later being awarded public contracts. In 2003 Ellison and Blair, then in his pomp, had a photo opportunity at Downing Street to mark a gift of supplies to 40 specialist schools. In tech circles this is known as “land and expand”. Oracle has since been contracted hundreds of times by the British government and earned £1.1 billion in public sector revenue since the start of 2022, according to data collected by procurement analysts Tussell.

While the Oracle founder was a late convert to US president Donald Trump, the company’s CEO, Safra Catz, worked on his transition team in 2016 and Ellison has been feted by him as “the CEO of everything” since he retook office. Trump named Ellison among the investors set to own a stake in TikTok’s US operations and the billionaire’s son, David, has taken charge of Paramount after a merger with Skydance, with the new conglomerate reported to be working on an offer for Warner Bros. Discovery Inc., which includes CNN.

As Blair moved from former prime minister to consultant-for-hire to the world’s political and business elite, his relationship with Ellison blossomed. The pair holidayed together off the Sardinian coast. In 2022, the former prime minister recorded a personal video message for Oracle lauding a “shared vision to advance global health”, by building unified electronic health records “stored in one place, where it can be analysed and utilised for the purpose of improving health outcomes.”

There is a reason why men whose fortunes are built on AI investments would target the UK, and that is the NHS and its unique population-level health data. Tech experts talk about Britain’s health records in almost hushed tones. While Europe and the US have some comparable health data sets – such as US veterans’ medical records – none have the depth and breadth of NHS records dating back to 1948 . Its potential commercial value, from drugs to genome sequencing has been estimated at between 5 billion and 10 billion dollars annually.

TBI, labour and NHS data

When Labour came to power last July it did so promising economic growth and an end to the UK’s productivity crisis. Just five days after Keir Starmer elected Blair told the TBI’s ‘Future of Britain’ conference that AI was the “game-changer” they were looking for. Within months, Starmer was parroting Blair’s language – and TBI was in the box seat of the government’s nascent AI policy pushing Oracle’s interests and its founder’s world view.

“There is a real hard sell going on here that says: ‘these kinds of gains are inevitable.’ But they are not,” said Professor Gina Neff of Queen Mary University London “TBI is not advocating for building that capacity within the NHS. They are saying: let’s outsource to our buddies.”

TBI was welcomed by a callow Downing Street operation . Peter Kyle, a former advisor in Blair’s second term, was appointed technology secretary despite little experience in the sector , and came into office calling for governments to show “a sense of humility” to Big Tech companies.

TBI had been laying the groundwork before Labour won power. Institute staff advised Starmer’s team in opposition. In May 2024, TBI wrote a report which called for “two radical actions” to fix Britain’s “data access problem”: create a “single front door” providing “seamless access” to NHS data; and host all of this data outside the NHS, while retaining government control of the programme.

Less than two months after Starmer’s win, TBI health policy director Charlotte Refsum was invited into the health department to meet digital policy chief Felix Greaves, documents obtained under FOI show. Greaves asked for her help in designing a giant public consultation on GP data and digital health ID. He told Refsum his department needed to “learn lessons” from previous health data scandals that had hardened public opinion against data-sharing with private companies.

Refsum was then given an official role in a government working group advising on data and technology policy in Labour’s 10 year plan for the NHS.

When that plan was published it contained both of TBI’s two radical ideas. The new “health data research service” would act as the front door to provide “a single, secure gateway to health and care data” and it would be mainly funded by the government but hosted by the Wellcome medical research charity.

TBI then threw a “summer party” around the launch of the 10 year plan at the London headquarters of the consulting giant McKinsey. The event was co-hosted by the chair of NHS England Penny Dash — herself an ex McKinsey partner — with “senior leaders from the NHS, private sector, pharmaceutical and biotech companies and investors” among the invited guests.

TBI also appears to have directly promoted Oracle products in its advocacy, even taking swipes at a competitor’s product. In an August 2024 paper on “preparing the NHS for the AI era”, TBI found “good reasons” for building new digital health records with an existing system run by Oracle. It also said that using a system run by rival Palantir – the £330million Federated Data Platform – would be “a controversial option” and that its product had “been slow to make progress, in part due to opposition from data-privacy groups.”

In a later paper, TBI recommended linking up data from the NHS, DWP and HMRC. All three bodies are Oracle clients, making the firm a clear frontrunner for potential new work.

A TBI spokesperson said: “We don’t advocate for technology solutions because we work with Oracle. We work with Oracle and other technology companies because we believe technology holds the key to the future. TBI is impartial when supporting government clients in technology delivery. The choice of technology provider is solely a government decision. TBI does not get involved in the procurement processes of our client governments with tech companies.”

Elsewhere, TBI staff were brought directly into government, while still on the institute’s payroll. Tom Westgarth was placed in the department of science, technology and innovation (DSIT), joining the small team working on the government’s AI Opportunities Action Plan. His salary was paid throughout by TBI. The action plan echoes many of TBI’s policy positions.

Documents also show Blair personally intervened to urge Kyle to embrace AI, telling him there was “no other solution to productivity, no other route to growth,” and that AI was “the UK’s economic future.” Blair also encouraged Kyle to meet with the Ellison Institute of Technology, a for-profit research institute that works via a group of internal companies based in Oxford funded by the Oracle supremo. In May, Kyle told DSIT officials to work with TBI on the nascent National Data Library (NDL) project. “Attaching the initial scoping work from TBI here,” the then technology secretary wrote in an email delivering the message to his team.

A UK government spokesperson said it engaged with a “wide range of stakeholders” in the development of policy, adding: “The government publishes, quarterly, details of ministers’ and certain senior officials’ meetings with all external individuals and organisations.”

The NDL was little more than an idea when Labour put it in their election manifesto. And there are still competing visions for what it should be. AI boosters foresee data from across government used for training and inference by Large Language Models; while many tech experts want to minimise privacy risks inherent in pooling data from so many sources and ensure that any benefits accrue to the UK.

“Of course the NHS should use data better to help patients and improve the health service,” said Cori Crider, honorary Professor at UCL Laws and the Executive Director of Future of Tech Institute. But what’s good for Larry Ellison may not be best for the NHS.”

“Given the vast sums being spent by Big Tech to shape UK policy on AI in the NHS, Labour’s science and tech leaders should reflect carefully about who benefits from these plans. Will the NDL return value to British patients – or will we end up handing our data, and most of the economic benefit, to another US Big Tech firm?”

Colonising Tech

Oracle and TBI’s connections are not just rhetorical. By 2023, joint retreats had become commonplace. At the institute’s headquarters at One Bartholomew Place in London, the teams would convene with executives from Oracle, Blair’s key advisor Macon-Cooney and Awo Ablo — who came to sit on the board of both TBI and Oracle – were sometimes present. Senior TBI employees have been hosted at Oracle’s headquarters in Austin, Texas, coordinated by a TBI employee whose role is to “scale and manage” the partnership with Oracle. Former staff recall that there were other earlier “hush hush” joint retreats at Ellison properties in the US.

“It’s hard to get across just how deeply connected the two [organisations] are,” a former TBI staffer said. “The meetings were like they’re part of the same organisation.”

The institute’s work outside the UK has often been preceded by Blair meeting with foreign leaders and his travel schedule has, if anything, intensified since leaving office. Among his paid assignments include Saudi Arabia following the murder of Jamal Khashoggi, and strategic advice to Kazakhstan’s former ruler after the country’s security forces shot dead protestors. This year it emerged that TBI staff were involved in discussions about drawing up a postwar Gaza plan that included creating a “Trump Riviera” on Palestinian territory.

What is less known is the extent to which Blair’s sustained influence with world leaders and infatuation with technology and AI are now geared towards marketing the services of Ellison. Conversations with more than a dozen former TBI employees who advised or drew up policy recommendations for governments across nine countries in the Global South reveal how their work ranged from explicitly promoting Oracle’s services and acting as a “sales engine” to recommending tech solutions that are potentially harmful or bizarrely divorced from local realities.

Multiple staff working for TBI during the Ellison cash injection speak of a sea change in culture. McKinsey consultants took senior positions and clashed with staff from humanitarian and development backgrounds. Ex-employees say this led to the institute pivoting away from writing reports and recommendations by well-meaning development experts towards pushing aggressive tech solutions across the board.

As TBI’s partnership with Oracle deepened, Oracle staff started to slide into TBI employees’ calendars and schedule meetings in order to find out what the organisation was doing in different countries and “scope out opportunities”, recalls one former staffer. Soon employees from the two entities were having regular joint calls.

This sat uncomfortably with many TBI staff, with some describing having to push Oracle’s technology despite knowing they were not in the best interests of the country in question, and even had the potential to cause harm.

The risk of so-called vendor- lock ing – tying a buyer to a single supplier – was a source of unease, with one former staffer saying that advising governments to use Oracle cloud services risked “trapping” and “indebting” them in systems that are “initially free but will start charging in future”.

Rwanda, a country where TBI has been present for more than 15 years, was so frustrated with Oracle that it issued a public tender in 2021 for a database management system, stating that it had been “experiencing a very high cost for support and licensing for Oracle systems and it would like to migrate to an affordable system”.

A TBI spokesperson said it did not get involved in the procurement processes of its client governments with tech companies.

The institute’s financial documents show “tech-related support” was offered to four out of five of its portfolio countries in 2022, compared with one in five in 2020, before the Ellison money. Former staff say the organisation’s “tech optimist” approach led to a failure to acknowledge potential disadvantages or dangers of technology solutions. Two employees recall that sections about risks in their draft reports started being removed by higher-ups.

Marvin Akuagwuagwu worked as a data analyst for TBI’s Africa Advisory unit in 2022 and 2023, focusing on Covid vaccine delivery. He said when he raised legitimate concerns, such as a lack of power supply and cyber security threats, when introducing new technologies to African countries these were dismissed by more senior colleagues.

“I’m an African, I have lived experience, and I’m saying these things, but I wasn’t being listened to. You have to downplay those negative things,” he said.

Akuagwuagwu also described how TBI would push technology and AI solutions on countries with far more fundamental issues to contend with: “They have issues around hunger, poverty, mass unemployment – and we’re getting them to commit towards some fancy projects like using drones and AI.”

In Ethiopia the disconnect was striking. With the country on the brink of civil war in 2020 TBI was working on a draft AI policy, seen by this investigation, which called for self-driving cars to be introduced. The paper cites the “enormous global market potential that lacks access to experimental settings” and the country’s “ideal terrain variations and regular real-world testing opportunities”.

One of the authors appears to catch the dissonance, writing in a visible comment: “So we’re saying test in Ethiopia because of its challenging terrain…?”.

Kenya’s capital Nairobi, with its UN headquarters and large diplomatic presence, was an important hub for TBI. But former staff complain that a previously broad range of work shrunk down to pushing Oracle technology as the solution. The tech sales approach became so explicit that a former senior staffer said TBI was becoming “a branch of Larry Ellison” that was seen to be “colonising” the local tech space.

Kenyan government officials had Oracle pitched to them so often, he recalled, that they would refer sarcastically to “uncle Larry”.

For TBI staff who joined before the Ellison era, some of whom have since chosen to leave, there’s widespread disillusionment. “There’s never been an organisation in the history of time that had so much resource, so many good people and achieved so little,” said one.

Back in London, some politicians are starting to feel disquiet about TBI’s influence on the Labour government. “Is TBI the trojan horse for American lobbying in the British political system?” asks Baroness Beeban Kidron, a crossbench peer who has also been a vocal critic of Labour’s approach to AI and copyright policy. “This government has consistently failed to understand the value of Britain’s data, in the NHS, in our museums, in our creative sector. They don’t understand because they listen to what TBI says – and what Oracle wants.”

PayPal

PayPal